In the December 2014/January 2015 issue of Petroleum Economist, Marakon shares an analysis on how E&P companies can reshape their portfolios for the long-term.

Introduction

The statement “all barrels are created equal” has never been further from the truth than today. In many cases, the risks and costs associated with asset acquisition, exploration and development have materially increased while price has been declining. As a result, exploration and production (E&P) companies are looking at asset portfolios with a far wider lens on cost and return, making the distinction between “good” and “bad” barrels significant.

In response to the dramatic market changes, the notion of value over volume is echoing across industry boardrooms. New technologies have created access to resources previously unavailable, while the cost of exploring and developing resources varies widely. Historically, the focus was on barrels discovered and production targets. There has now been a shift towards return on capital, return on risk and value creation.

While the industry is wrestling with how to leverage the boom in oil and gas capacity, investors are looking for clarity on the investment proposition. This is a challenging question for the leadership teams of oil and gas companies to answer. Companies such as ExxonMobil, Shell and BP have started to build an investor proposition around delivering sustainable and predictable cash flows. This model suggests equity investors are willing to trade capital appreciation for a more secure stream of cash flow, one might say “bond like.”Despite the stated intent, in our experience, E&P companies are not set up to deliver on this proposition.

Built into the DNA of oil and gas companies is the quest for producing / developing barrels, an ability to open new frontiers and take risk on complex bets that offer the chance for outsized returns. However, explorers and upstream managers whose goal is to find and extract, think differently than managers of an absolute return fund. Consider the clearest example: the rebirth of North America as the world’s leading producer.

In spite of the differences between the worlds of E&P and asset management, we asked ourselves a simple question:

Could adopting the mind-set of the asset management world represent an opportunity for E&P companies?

By creating a new evaluation of the capital, risk signatures and return of the E&P assets, leadership teams can optimise the shape of the portfolio far more dynamically than in the past. If the appetite for total risk started to hit the high range of the company and investor, leadership could pare back certain assets or reshape its view of acquisition and divestiture candidates in order to enhance the predictability of the company’s cash flow. Conversely, if more risk appetite existed than was being used, leadership could choose a path on the higher bounds of the risk-return continuum.

This asset management mind-set would allow for a better dialogue between the company centre and those directly responsible for the E&P assets in the portfolio.

We recently implemented this idea and premise with several oil and gas companies and found it has been a powerful mechanism for materially upgrading the strategic dialogue inside E&P companies and for delivering more clarity to investors. This article shares the learning from our recent work.

Elements of the New Approach

The case for a new mind-set

Ingrained in the upstream culture is an appetite for risk-taking and a focus on finding the next big thing. In this mind-set, success is defined by creating the most value or finding the most resources relative to peers.

However, as the dialogue with investors changes and predictability of cash flows becomes a primary objective, the definition of success must change accordingly. The new objective becomes a need to increase the predictability of sustainable cash flow while allowing for sufficient upside. In other words, any type of value creation objective must come with a minimum output constraint on cash flow, similar to the addition of very low-risk assets such as treasuries into a financial portfolio.

Adding predictability constraints requires a different mind-set to the conventional one of explorers, where success now becomes hitting cash flow targets consistently. Outperforming the competition is secondary. It requires a deeper discussion on the trade-offs between return on risk, affordability and cash flow timing across a portfolio of assets, in addition to the usual assessments of whether each opportunity or project is desirable.

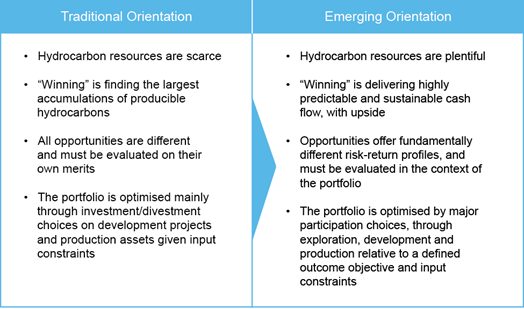

To put it another way, this approach requires executives responsible for shaping the upstream portfolio to think like absolute return fund managers. This requires a major mind-set adjustment in a world where the upstream has just begun to move away from a volume-based objective. Figure 1 illustrates the magnitude of mind-set change implied.

Figure 1: Shift in mind-set

This new mind-set has major implications for resource allocation and performance management. As a result, it needs to take hold not only amongst the upstream management team, but also in the corporate planning process. The premise is that different portfolios, made of up different asset types, will have different distributions and probabilities of outcomes depending on cash flow expectations and correlation of risk embedded in each combination.

So how can management teams practically apply this new mind-set to strategic decision-making?

Determining the right portfolio “puzzle pieces”

Strategic dialogues related to portfolio shapes in oil and gas companies tend to fall prey to the “clouds or weeds” problem. Either they are too “thematic” (“the clouds”) and therefore difficult to ground analytically (e.g. “more liquids, less gas,”) or too focused on one individual project (“the weeds”) and therefore lack a true portfolio perspective. In order to solve this problem and create a set of analyses to test different portfolios, it is both possible and helpful to abstract from individual projects upwards to generic “asset classes” composed of economically similar projects. Such “asset classes” have economic signatures which are internally similar and consistent but externally distinct from others. Figure 2 shows an illustration of the cash flow profiles and returns of 10 “asset classes.” (The data have been modified to preserve confidentiality.)

Figure 2: Illustration of “asset classes” and their distinct economic signatures

Source: Marakon

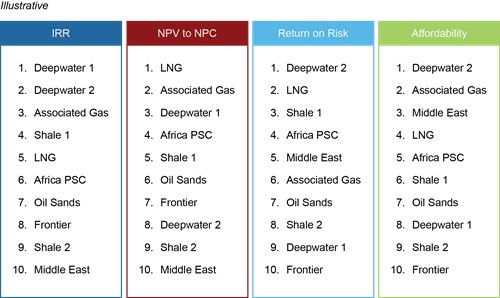

This methodology introduces a happy middle ground, based on a grounded analytical foundation that is nevertheless suitable for higher-level decisions around portfolio shape. It also provides the analytical inputs for the development of an asset-based portfolio model. Importantly each “puzzle piece” is assigned an economic profile against a range of affordability, value creation and risk measures that are derived from a database of internal and external project experiences. The impact and likelihood of risk can be quantified to provide a probabilistic view of each asset. As the foundation for a forward-looking portfolio discussion which will have an impact on operations, each puzzle piece can be ranked against a series of metrics to deepen executive understanding of sum-of-the parts performance against a specific objective function. This could be value creation per unit of investment, affordability, cash flow timing or return on risk. Figure 3 demonstrates the ranking of different puzzle pieces against key metrics.

Figure 3: Ranking of illustrative puzzle pieces under different objectives

Source: Marakon

The number of puzzle pieces can vary depending on the client’s desired granularity and / or sophistication. Our analysis and experience suggests there are between 10 and 15 main puzzle pieces in the world today that exhibit substantially different economics and are suitable for portfolio design work at the strategic level. Building alignment across the executive teams (i.e. upstream, group planning and finance) on the right ones is critically important to arrive at a trusted set of economics for deeper and more valuable strategic dialogues. This alignment process is often underestimated. Establishing this fact base is a valuable process in its own right.

Understanding risk and maximising true diversification benefits

Once the economic signatures for each puzzle piece are in place, a portfolio model can be created to simulate different outcomes associated with dialling-up or dialling-down concentration in any particular asset. However, even more depth is needed to ensure the issue of risk correlations is adequately addressed. Some risks (e.g. oil price) are broad, while others (e.g. geological) are narrower. The risk signatures of different puzzle pieces need to be deconstructed with two end goals—to quantify sources of risk common to all assets and sources of risk specific to individual assets. In doing this, managers can precisely quantify the benefits of different combinations of assets, and be more deliberate and precise about optimising the level of diversification. The benefits of any diversification are maximised when risks are not correlated between puzzle pieces. For instance: 1) Price e.g. Brent vs. Henry Hub Gas; 2) Failure e.g. Gulf of Mexico vs. Oil Sands 3) Cost e.g. NA wages vs. international rig rates 4) Delay e.g. deepwater rig delays vs. unconventional supply chain.

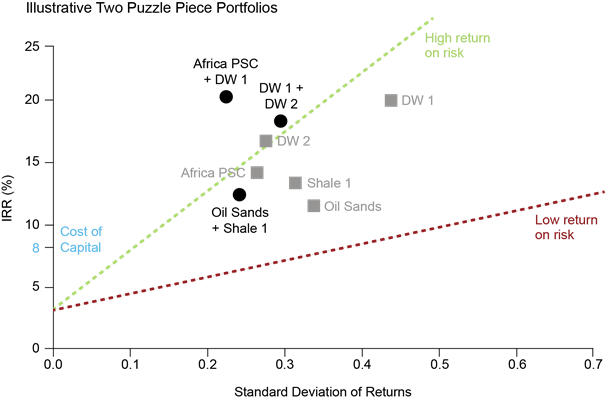

In addition to correlations across risks, there is also a need to look at correlations betweenthem. For example, cost and delay risk are typically highly correlated. Any benefits depend on how sensitive different puzzle pieces are to individual risk types. For instance, diversification benefits are reduced between a portfolio of Gulf of Mexico assets and North American Heavy as both share a high sensitivity to oil price, despite differences in below ground risk. Figure 4 shows the impact of creating simple portfolios using two puzzle pieces and the impact it has on the overall risk vs. return profile vs. individual “puzzle pieces.”

Figure 4: Diversification impact on “simple portfolios”

Source: Marakon

Developing a portfolio simulation model

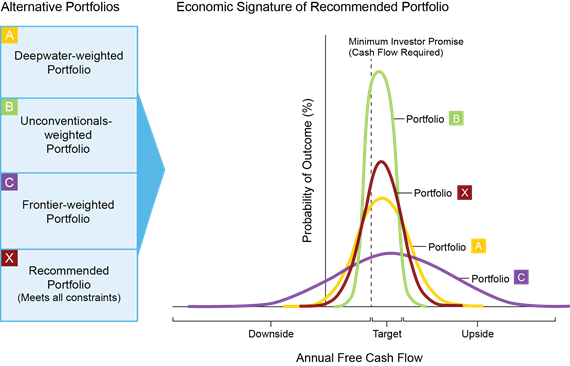

Optimising a portfolio to a set of “outcome” objectives is based on the premise that there is an optimal level of diversification for the future portfolio based on the agreed objective function. If the inputs are “unconstrained,” achieving the desired outcome is that much easier. The challenge, of course, is that inputs are always constrained, be it by capital, resource availability or technology. By understanding the desired output constraint, for example 85% probability of maintaining a certain level of cash flows into the future, in combination with a defined set of input constraints (exploration capital expenditure, development capital, resource availability), a simulation model can be created to provide insight about which portfolio shape is best for any given company. This simulation model can then provide input into the complex choices and trade-offs associated with managing the long-term portfolio shape. Figure 5 illustrates how such a simulation model has been used to create four alternative portfolios, each optimised around a different metric through a distinct weighing of puzzle-pieces, and how these portfolios compare against the probability of delivering a minimum cash flow and yielding upside value. These alternatives are then used as an input to the strategic dialogue on participation choices.

Fig. 5: Portfolio outcomes and shape

Source: Marakon

Upgrading the dialogue process

While this methodology is grounded in deep analytics and delivers precise direction on an “optimal” asset portfolio under different scenarios, the real benefit arises from its impact on the quality of strategic dialogues in the E&P world.

We have worked with many clients to deploy this approach and have observed that the process creates more insights and upgrades the nature of internal debate and dialogue. Each step in the process, be it alignment on the objective, insight on the cash flow patterns of different puzzle pieces and their economic signatures or a discussion on risk correlation, alone led to a materially higher quality of executive discussions.

Through using this approach, we have observed that E&P management can make earlier and more decisive value-based portfolio decisions that have a material effect on the exploration budget and business development priorities. The approach also provides a “bridge” between the corporate objectives to meet changing shareholder demands and manage cash flow, and the upstream management teams’ goal to find and develop resources. This provides a critical mechanism for aligning around the company strategy and decisions on resource plays.

Summary and Learnings from Applying the Approach

This new approach has proved to be a powerful way of adding value to the strategic dialogue on managing the E&P portfolio. It is comprised of five key ingredients: 1) alignment on the objective function (i.e. the targeted outcome); 2) creation of “asset types” or puzzle pieces based on a set of internal and external experiences with different projects; 3) an understanding of how risks are correlated between different puzzle pieces, and across the portfolio; 4) the development of a simulation model to model different portfolios and their outcomes; and 5) a dialogue process around the approach, the interim outputs and the portfolio shape decisions.

Finally, if Big Oil is to keep pace with changing market dynamics and new investor demands, then additional capabilities, analytical tools and processes must be added and integrated into the existing decision-making models.