Introduction

Growth is central to the strategic agenda in all consumer products companies. As the growth in core product markets slows down, companies across sectors as diverse as luxury, brewing, skin care, beverages, and grocery look for growth potential in adjacent areas.

Marakon reviews the key challenges faced, lessons learned, and implications.

Adjacencies – Definitions

Adjacencies are new business areas that most often build from a company’s established assets. In the branded consumer products sector, a company’s brands are often its most critical assets. Existing brand assets can be applied to adjacent areas in different ways

In this commentary, we address the challenge of taking existing brand assets into adjacent category and / or product markets. While this type of adjacency can on the surface appear relatively simple to effect successfully, businesses we work with and observe often face material challenges.

Key Challenges Faced

The strength of an existing brand proposition is not a sufficient condition for success in adjacent category and product markets. Our experience suggests that 8/10 initiatives of this type fail, primarily due to ineffective balancing of Marketing “ambition” with General Management “business pragmatics and economics.” This dynamic manifests itself in many ways inside businesses:

Lack of clarity on the core objective

Companies wishing to take an existing brand into new product or category markets are often unclear on whether the adjacency play is expected to deliver material growth to the business or simply a new, profitable, but niche position with substantive effect on existing brand equity.

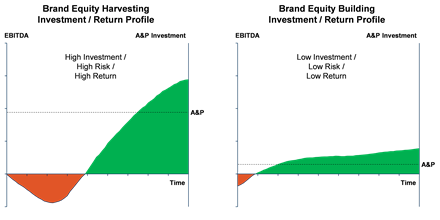

Entering an adjacency for the purpose of delivering material growth usually involves marrying existing consumer brands with products or categories that will inherently have mass appeal. This kind of play requires the usage of brands with strong existing equity, as the adjacency plays by their very nature will be leveraging and “harvesting” the existing equity. Marakon calls these instances “brand equity harvesting” adjacencies. Given their size and wide target audience, getting into brand equity harvesting adjacencies often involves significant, relatively high risk, up-front investment, sometimes in the form of capital expenditure if the new product / category requires a different manufacturing process than the core product range, and almost always in the form of a major marketing campaign. The resulting financial profile of these opportunities thus most often looks like a standard J-curve and their risk / return profile is high / high.

Brand equity building adjacencies, on the other hand, are entered as a way to build a small, incrementally profitable business, while considerably strengthening brand credentials. These kinds of adjacent areas often have associated A&P costs that are much lower than for brand equity harvesting adjacencies. Their most typical investment profile is that of a small investment and quick, step-wise uptick in top-line, with a subsequent flattening as the niche position is established. The majority of the benefit is seen on the brand equity building side, and their risk / return profile is low / low.

Illustrative profiles of the two most common types of brand to product / category plays are shown on the next page:

In our experience, consumer products manufacturers are frequently not clear enough on what they expect their adjacencies to deliver, and therefore what a desirable or expected investment profile and acceptable level of risk should be. At a minimum, this lack of clarity on the core objective of the adjacency play can confuse the dialogue between NPD / Marketing teams and General Management on whether or not to consider a certain adjacency play. It can make business cases appear either unrealistic or unattractive, senior executives with a good intuitive sense of what is likely to work in a market nervous, and marketing / NPD teams disappointed because their “best ideas” do not receive the financial backing they need.

Additionally, we often see companies enter brand equity harvesting adjacencies without properly investing behind them, only to quickly withdraw products from the market when projections are not met. Given the wide target audience for these adjacencies, they almost always require significant A&P investment to drive awareness and trial; consumers need to know about a new product before they can purchase it. Both the investment and time needed to build this awareness must be built into adjacency launch plans to ensure that companies do not give up on a new adjacency too soon or for the wrong reason.

Lack of material competitive advantage in the adjacency

Companies are often convinced to enter adjacencies due to the sheer size of the opportunity. They see large markets, high growth rates, and other companies finding success there – in other words, they observe a lot of “headroom” and believe fast entry will allow them easier access to that headroom before others come to the game.

Unfortunately, looking at headroom alone is not enough. Companies must instead look at accessible headroom i.e. headroom they could actually win, because they would be bringing something substantially differentiated to the market that will drive real consumer preference. This may be the features of the product itself, the emotional equity of the brand, the brand-product-price combination, greater distribution than the competition, or all of the above, but an adjacency will only be successful if the company has a material source of differentiation and competitive advantage.

In 2007, cereal giant Special K launched Special K20, a range of flavoured bottled waters with added protein, to position the brand in the rapidly growing flavoured water category. But Special K had no tangible competitive advantage in the heavily competed water space vs. existing players e.g., Vitamin Water. Resulting low sales led to an early product exit.

Lack of alignment with existing brand image

Marketeers tell us to protect a brand’s image above all else, but companies often forget this basic lesson when attempting to take brand assets into adjacent categories or products. Again, they often get caught up in the size of the opportunity, and do not think deeply enough about how the adjacency relates (or not) to the core “truths” behind their brand assets. This can be particularly dangerous – consumers may not purchase the new product, but the core business may also be eroded if consumers lose overall trust in the brand as a result of the adjacency play.

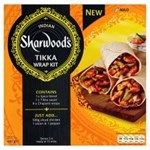

Sharwood's, the Chinese and Indian food producer, launched Wrap Kits in 2012, allowing consumers to eat their Asian cuisine in the style of a Mexican burrito. The play harmed the brand’s ethnic credentials, resulting in decreased loyalty from existing consumers on the core offer.

Sharwood's, the Chinese and Indian food producer, launched Wrap Kits in 2012, allowing consumers to eat their Asian cuisine in the style of a Mexican burrito. The play harmed the brand’s ethnic credentials, resulting in decreased loyalty from existing consumers on the core offer.

Smoothie maker Innocent has a strong brand proposition around delivering natural, delicious and healthy food. In 2003, the brand launched Juicy Water, a range of flavoured waters with six teaspoons of sugar in every bottle – a far cry from the brand’s healthy image. Loyal consumers felt alienated, and Innocent had to spin off the range a few years later.

While “brand equity harvesting” is clearly a way to generate growth, if the brand is stretched too far, the positive impact can quite easily be diluted or even be dangerous to the core business.

Lack of material progress on adjacencies due to organisational constraints

As discussed above, there are certainly many dangers in having unclear expectations regarding the financial profile of product / category adjacencies. There are also obvious dangers in launching in the “wrong” adjacencies. Equally however, there can be dangers in not trying enough new ideas.

A popular cooking sauce company structured its organisation in a way that made no separation of resource between its core business and proposed adjacencies. As a result, adjacencies were never pursued properly, as the team spent over 95% of the time focused on fire-fighting in the day-to-day business. Additionally, senior management was not prepared to allocate financial resource to ideas with long, often uncertain delivery profiles, especially when trading those off vs. incremental resource into the core business, with an inherently shorter delivery profile.

However, the equity of their core brands was slowly beginning to erode, consumers were documented as feeling the brand was “staid” and “not delivering anything new” to the market, and smaller, innovative players were entering the market and starting to carve out profitable niches. Business as usual trumped adjacencies every time, until the company observed that the lack of front-footedness was having a detrimental impact on their brand assets and market position with consumers.

Lessons Learned and Implications

Clear ingoing objectives help set expectations and financial framework

Brand equity harvesting adjacencies have a very different investment and return profile than do brand equity building adjacencies, and it is important for companies to recognize which type of adjacency they are pursuing in order to make more informed, confident decisions on which adjacency to pursue, how much money to invest behind it, and what kind of return profile to expect. Companies must have realistic expectations. When pursuing brand equity harvesting adjacencies companies must be patient– they are not going to help the bottom line overnight. Equally, a brand equity building adjacency is not going to be a financial game- changer, but it might be worthwhile to pursue nonetheless because of its effect on the brand.

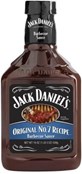

Jack Daniels, the Tennessee whiskey maker, launched a line of barbecue sauces in 2006. Many consumers already used the company’s liquor in their homemade sauce recipes, and Jack Daniels leveraged that fact and their existing brand equity to enter the rapidly growing sauce and marinade market. Given this adjacency’s novelty, significant upfront A&P investment was required to create awareness and drive trial. Significant returns did materialise, but the whiskey maker needed to be patient. Conversely, Jack Daniels launch of Tennessee Honey in 2011, the brand’s first flavoured variation, allowed the company to enter the inherently smaller but higher margin area of flavoured liquor.

Jack Daniels, the Tennessee whiskey maker, launched a line of barbecue sauces in 2006. Many consumers already used the company’s liquor in their homemade sauce recipes, and Jack Daniels leveraged that fact and their existing brand equity to enter the rapidly growing sauce and marinade market. Given this adjacency’s novelty, significant upfront A&P investment was required to create awareness and drive trial. Significant returns did materialise, but the whiskey maker needed to be patient. Conversely, Jack Daniels launch of Tennessee Honey in 2011, the brand’s first flavoured variation, allowed the company to enter the inherently smaller but higher margin area of flavoured liquor.

Real competitive advantage is a necessary ingredient for success

When a company enters an adjacency where it does not have a distinct competitive advantage, it almost always fails. Very rarely is the brand alone enough to provide this advantage. Rather, consumers must believe that the product or brand is better, or better value for money, or more widely available and therefore more noticeable.

Frito-Lay, owner of brands like Lay’s, Doritos, Ruffles and Tostitos, believes its brand stands for convenient and delicious snacks for enjoyment. In the 1980s, Frito-Lay launched a line of dips that were specifically created to harvest the brand equity by complementing its existing chip range (e.g., Tostitos salsa, Frito’s dip), an adjacency move that has been very successful. The dips range both reinforced the brand’s proposition around delicious snacks, and successfully leveraged the company’s distribution advantage in the snack aisle.

Frito-Lay, owner of brands like Lay’s, Doritos, Ruffles and Tostitos, believes its brand stands for convenient and delicious snacks for enjoyment. In the 1980s, Frito-Lay launched a line of dips that were specifically created to harvest the brand equity by complementing its existing chip range (e.g., Tostitos salsa, Frito’s dip), an adjacency move that has been very successful. The dips range both reinforced the brand’s proposition around delicious snacks, and successfully leveraged the company’s distribution advantage in the snack aisle.

Linking adjacencies clearly to the existing brand, is paramount

When consumers think of a well-known brand, a very specific image and proposition comes to their mind. When the brand deviates from this image, consumers are often confused and disappointed. It is therefore critical that any new adjacency entered links clearly to the existing brand proposition.

Innocent learned from its earlier failure with Juicy Water, and sought to harvest the brand equity and appeal to a larger audience by launching Veg Pots, a range of chilled, single-serve meals, all made with pure, healthy ingredients and no additives. Veg Pots strongly reinforced the brand proposition around delivering natural, delicious and healthy food, and recorded £15m in retail sales in the UK in the first year after launch.

If a company firmly believes that a particular adjacency is the way of the future but it does not link closely enough to the existing brand, the company should strongly consider entering the space under a new brand. Business leaders are often hesitant about launching new brands given the investment, time and risk required to brand build, but this is in fact a less risky option than entering a mismatched adjacency and potentially damaging the existing brand equity.

As we saw in the examples above, it is critical for companies to be competitively advantaged in adjacencies and for adjacencies to align with brand image, but there are a number of other criteria which successful adjacencies also need to meet. Ensuring that potential adjacencies meet the below list of key criteria greatly minimizes the likelihood of failure:

Diligent evaluation against entrance criteria can give an objective read on likelihood of success

- A direct consumer need should be addressed, preferably where there is a market gap

- The organizational capability to execute should be in place or be able to be built up quickly

- A material sales uplift should be predicted for brand equity harvesting adjacencies

- Profit margins should be equal or higher than the company’s target over time

- A notable uptick in brand perception should be expected for brand equity building adjacencies

- The magnitude and timing of investment should fit with the company’s other financial commitments

- The adjacency should carry an acceptable amount of risk

Smart “toe in the water” entry strategies can help mitigate inevitable risk

Once companies select adjacent areas to pursue, they are then faced with the challenge of effectively managing entry and scale-up while minimising financial and operational risk. Rather than going “full steam ahead” into a new adjacency, companies should enter new adjacencies in a manner that allows them to in some way judge performance before fully committing substantial financial resource behind them. Common ways to do this are by using licensing agreements, by outsourcing production to a partner, and / or by launching in a small test market to gauge consumer reaction. Over time, if these adjacencies prove successful with consumers and the financial returns start to look attractive, manufacturing can then be brought in house, and / or a broader launch can be executed.

Wonder Bread, the white sliced bread beloved by children across North America, saw a promising adjacency in the lunch space. Sandwiches made with fluffy Wonder Bread were often crushed inside children’s lunch boxes, turning off some consumers. To remedy this – and benefit from added brand placement in the supermarket aisle – Wonder Bread sought to create a plastic storage container that perfectly fit a sandwich made with its bread. However, the company did not have the production capabilities to do so, and the capital expenditure required for this was significant. Purchasing the equipment was judged to be too risky, so instead, the company licensed its brand to a partner who could make the Wonder Bread Sandwich Packer.

Wonder Bread, the white sliced bread beloved by children across North America, saw a promising adjacency in the lunch space. Sandwiches made with fluffy Wonder Bread were often crushed inside children’s lunch boxes, turning off some consumers. To remedy this – and benefit from added brand placement in the supermarket aisle – Wonder Bread sought to create a plastic storage container that perfectly fit a sandwich made with its bread. However, the company did not have the production capabilities to do so, and the capital expenditure required for this was significant. Purchasing the equipment was judged to be too risky, so instead, the company licensed its brand to a partner who could make the Wonder Bread Sandwich Packer.

We see another example of mitigating the risk of entering a new category adjacency through licensing in Special K. The brand is famous for its Special K Challenge, which promises that consumers can lose six pounds in two weeks by eating the brand’s cereals every day.

We see another example of mitigating the risk of entering a new category adjacency through licensing in Special K. The brand is famous for its Special K Challenge, which promises that consumers can lose six pounds in two weeks by eating the brand’s cereals every day.

But this promise only holds for people who eat the recommended serving size, and many consumers had difficulty with portion control, pouring too much cereal into their bowls. The company wanted to make it easier for consumers to follow the Special K Challenge by selling measuring cups for quick and easy portion control. However, the company did not have the manufacturing capability to produce these in house, and purchasing this equipment before seeing how demand materialized was deemed too risky. Instead, Kellogg’s licensed the Special K brand to a partner who could produce the measuring cups.

Critical to keep the adjacency funnel fresh

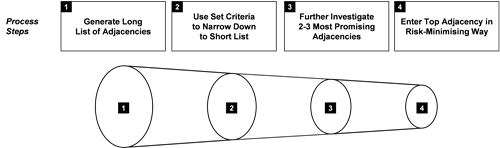

Clearly, the process of generating, screening, and executing a risk-mitigating market entry in an adjacent product or category can unfold over a long period of time.

Pressure on growth however is constant, and companies still need to find ways to be nimble and aggressive without taking undue risk. One way to strike the right balance between ambition, speed to market and risk mitigation is to work very hard to keep the early stages of the adjacency funnel fresh, so 1-2 ideas are always close to being launched in market.

New ideas can be compiled from different sources:

- Adjacencies we observe as attractive due to changes in consumer tastes or preference

- Adjacencies that represent close substitutes to the products we currently make

- Adjacencies that represent product areas used in conjunction with our current products

- Adjacencies that build off of successes in other parts of the wider business portfolio

- Adjacencies we think our closest competitors may enter or new entrants have already penetrated

- Adjacencies we believe may open up given new technologies or capabilities we have recently acquired

Organisational separation from “business as usual” activity is a final prerequisite for success

Adjacencies are new, they are different, and they should not be managed in the same way or under the same organisational and resource umbrella as the core business. As seen in our cooking sauce example, adjacencies will not receive sufficient attention and resource if they are run by people responsible for running the core business, or if they are treated as simple line extensions rather than small new businesses.

While it may vary from company to company, Marakon generally believes that 10-20% of total resource (time, capital, talent) should be parked for the exploration, testing, and pursuit of adjacent areas. Individuals working in the earlier stages of the adjacency funnel (generally Strategic Marketeers or New Product Developers), should have a skills bias towards innovation and “out-of- the-box” thinking, and also be comfortable using consumer research methods relevant for exploring relatively untested areas (e.g., conjoint analysis, concept testing). Additionally, it is critical for these individuals to maintain strong working relationships with people in the Sales, Marketing, Supply Chain, Finance and Strategy functions, and get input from these other functions early and often.

As long as the final decisions on selection and funding of adjacencies are made with a general management mind-set using the criteria and approach we have discussed at length in this article, we believe the right balance of “good” risk-taking and business pragmatics will be struck.

Conclusion

Though challenging, it is possible for companies to develop a strong capability around entering adjacent product / category markets with existing brands. The critical success factor is finding a way to organizationally balance Marketing “ambition” with General Management “business pragmatics.”